Draft

There is surprisingly little discussion of whether teletransportation can be verified (or falsified) empirically. I think the question is more interesting than most people realize.

There is surprisingly little discussion of whether teletransportation can be verified (or falsified) empirically. I think the question is more interesting than most people realize.

The issue is whether the person who emerges from the transporter is the same person as the one who entered; or just a freshly-minted lookalike, the one who entered having died. For my purposes, I will assume—pace someone like Parfit—that this is a legitimate issue, concerning two genuinely distinct possibilities, the only question being which one is true. The line I wish to pursue, thus taking the question at face value, is whether the answer to it can be determined empirically.

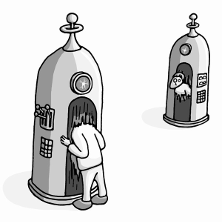

Empirically speaking, what everyone agrees on is this: we cannot determine the answer “from the outside,” i.e., from a third-person vantage point. It would be futile to observe someone else enter the machine and thereafter “check” if that same person emerged on Mars: there would be no telling if the person who emerged was the same as the one who entered. The interesting question, however, is whether we can determine the answer “from the inside,” from the first-person point of view. At risk to your own life, could you not try the machine out for yourself in order to see what happens?

This simple first-person check does appear to work in at least one type of case. If there was such a thing as an afterlife, then, if the machine killed you, you’d find yourself waking up in some fiery place like purgatory (say), and you’d realize (let’s presume) that you were dead. Thus:

Kathleen V. Wilkes, Real People: Personal Identity without Thought Experiments. (1988), p. 46, n. 28.

Available at the Internet Archive.

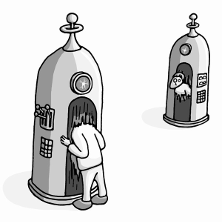

Given Wilkes’s aversion to thought experiments, she may not have approved of my use of this passage.Captain Kirk, so the story goes, disintegrates at place p and reassembles at place p*. But perhaps, instead, he dies at p, and a doppelgänger emerges at p*. What is the difference? One way of illustrating the difference is to suppose there is an afterlife: a heaven, or hell, increasingly supplemented by yet more Captain Kirks all cursing the day they ever stepped into the molecular disintegrator.

This is Kathleen Wilkes, artfully highlighting the uncomfortable possibility conveniently left unmentioned in Star Trek. Her words are to our purpose too: if the transporter killed you, then you could discover this by trying it out, assuming there was such a thing as an afterlife. Of course, if there was no afterlife, then you’d learn nothing: you’d just lose consciousness and it’d be over. But the potential for falsification is clearly there since we cannot in general rule out an afterlife.

If falsification of teletransportation is thus possible, what of verification? What happens if the machine worked and really did “send” you to Mars? You’d press the button and find yourself waking up on Mars. Would this assure you in a parallel way that teletransportation was real and that you really had been transported to Mars? Take Parfit’s story above:

I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all. Even the cut on my upper lip, from this morning’s shave, is still there.

I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all. Even the cut on my upper lip, from this morning’s shave, is still there.

Would this satisfy Parfit himself, if no one else, that the machine had worked? Would it constitute an empirical verification of teletransportation?

As we know, the matter is not that simple, because of the following obvious snag. Even if the machine did work, and you did find yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether you were the person who entered the machine, or whether that person died, and you were just a freshly-minted lookalike with false beliefs of having previously entered the machine. After all, anyone—real or copy—who emerged on Mars would “remember” having earlier entered the machine on Earth. So you’d be none the wiser as to whether you were “real” or “copy,” and thus none the wiser as to whether the machine had really worked.

For example, in Dan Dennett’s story, a woman on Mars with a broken spaceship uses a teletransporter to get back to Earth. Upon reuniting with her daughter Sarah, it “hits her”:

Am I, really, the same person who kissed this little girl good-bye three years ago? Am I this eight-year-old child’s mother or am I actually a brand-new human being, only several hours old, in spite of my memories—or apparent memories—of days and years before that? Did this child’s mother recently die on Mars, dismantled and destroyed in the chamber of a Teleclone Mark IV? Did I die on Mars? No, certainly I did not die on Mars, since I am alive on Earth. Perhaps, though, someone died on Mars—Sarah’s mother. Then I am not Sarah’s mother. But I must be! The whole point of getting into the Teleclone was to return home to my family! But I keep forgetting; maybe I never got into that Teleclone on Mars. Maybe that was someone else—if it ever happened at all. Is that infernal machine a teleporter—a mode of transportation—or, as the brand name suggests, a sort of murdering twinmaker?

Am I, really, the same person who kissed this little girl good-bye three years ago? Am I this eight-year-old child’s mother or am I actually a brand-new human being, only several hours old, in spite of my memories—or apparent memories—of days and years before that? Did this child’s mother recently die on Mars, dismantled and destroyed in the chamber of a Teleclone Mark IV? Did I die on Mars? No, certainly I did not die on Mars, since I am alive on Earth. Perhaps, though, someone died on Mars—Sarah’s mother. Then I am not Sarah’s mother. But I must be! The whole point of getting into the Teleclone was to return home to my family! But I keep forgetting; maybe I never got into that Teleclone on Mars. Maybe that was someone else—if it ever happened at all. Is that infernal machine a teleporter—a mode of transportation—or, as the brand name suggests, a sort of murdering twinmaker?

So it seems that, if the machine worked, you could not discover this even by trying it out for yourself. This may be why the question is seldom discussed of whether teletransportation is subject to empirical test. At least where verification of the phenomenon is concerned—and this is arguably the more important case—the answer may be thought to be obviously no.

This may be thought to settle the matter but, in fact, I will suggest now that the foregoing sceptical thoughts are somewhat confused and essentially incorrect. If the teletransporter works, I believe that you can verify this by trying the machine out for yourself. Not always, as I will explain, but at least some of the time, when conditions are favourable in a certain way.

To recapitulate, the sceptic claims that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether your memory of having entered the machine was genuine or false. You wouldn’t know if you were the person who originally entered the machine, or just a freshly-minted copy with a false memory of having done so. So you’d be unable to tell if the machine had worked. (If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.)

To recapitulate, the sceptic claims that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether your memory of having entered the machine was genuine or false. You wouldn’t know if you were the person who originally entered the machine, or just a freshly-minted copy with a false memory of having done so. So you’d be unable to tell if the machine had worked. (If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.)

The alleged threat here is the false memory. As you wake up on Mars, the thought that you might be the copy with the false memory is supposed to give you pause. But for this possibility, you could just go by your memory of having entered the machine and judge that the machine had worked. But—wait—you might be the copy! Then your memory would be false and the machine would in fact have failed! You’d be in danger of making the wrong judgement here if you went by your “memory.”

This line of thought could use a little clarification, since it should be obvious that the only person, really, who could end up making the wrong judgment here is your copy, and not you. You yourself could never be “in danger” of judging wrongly that the machine had worked, since you were the one who entered the machine. The sceptic’s point, rather, is better expressed as follows. Being unable to tell whether you were real or copy, you'd be forced to assume a split personality, à la Dennett's protagonist above, flitting between the perspectives of original subject and copy, the former wanting to declare that the machine had worked, the latter otherwise. Each would veto the other's predilection, as it were, and so you'd end up the proverbial ass, paralyzed on the matter of whether the machine had worked. You wouldn't be able to say, either way.

Having clarified that, the weakness in this reasoning may perhaps be evident. It presupposes that your copy would be just as concerned (as you would be) about whether the machine had worked or failed, i.e., would care to know the answer, would want to make a reasonable judgment on the matter, would not want to get it wrong, and so on. Note that this presupposition is substantial in the sense that it was not built into our story. In contrast, that you, the person who originally entered the machine, would care about these things was given in the story: in particular, should the machine work, you'd want to know that it was really you who was waking up on Mars, and thereby that the machine had indeed worked. After all, you were trying to see if teletransportation could be verified in the first-person. But that your copy, should he awaken on Mars, would likewise be interested in knowing that he was, in fact, the copy, and thereby that the machine had failed, while consistent with our story, is not actually essential to it.

To see how this matters, imagine that your copy, should he awaken on Mars, would actually rather not know that he was the copy and that the machine had failed. This might be the case if, for instance, you yourself were the sort of person who would be aghast at the thought of being a copy, and would rather labour under the misapprehension that you were real than face the nightmare of being a copy. (Your copy, should he subsequently materialize, would then inherit this disposition.) Under these circumstances, the previous “threat” of the false memory would vanish. For—recall—what was supposed to give you pause, as you wake up on Mars, was the thought that you might be the copy with the false memory: there was a danger of “you” judging wrongly that the machine had worked if you went by your memory. But if the copy does not care about judging thus wrongly, this “danger” no longer exists. Nothing now stops you from going by your memory and judging that the machine had worked. In particular, the thought that you might be the copy would no longer stop you.

In a case like this, I submit that you'd be able to verify that the machine works, if it does work, by trying it out for yourself. You'd enter the machine, press the button, and, upon waking on Mars, would grasp (for the reasons above) that you may just go by your memory and judge that the machine had worked—which we may presume you to do. Your judgment would be bound to be correct, as before, because you were the one who entered the machine. Moreover, the correctness of your judgment would be no fluke: luck is nowhere involved. Given these considerations, it is natural to ask whether you may be said, in this case, not merely to have judged correctly that the machine had worked, but also to know that the machine had worked (and thus to have verified the reality of teletransportation). Having considered the matter carefully, I believe that the answer is yes, although this is not obvious and requires some justification. Notoriously, there is a gap between judging correctly and knowing, and it may seem that the gap is not bridged in our case. Consider, in particular, our previous concession that you'd be unable to tell, upon waking, whether you were the person who originally entered the machine or the copy with the false memory. This does not appear to be vitiated in our modified case. Thus, notwithstanding your distaste at the thought of being the copy, being the copy would remain indistinguishable from being the original subject, so how could you tell which one you were? And if you couldn't tell, then you wouldn't really know whether the machine had worked or failed. Granted, you'd be bound to judge correctly that you were the original subject and that the machine had worked, but, for all that you'd know, for all that you'd be able to tell, you'd be the copy with the false memory, laboring under the misapprehension that you were real.

This concern is indeed very natural, and virtually the first thing that comes to mind, but I believe that it also rests upon a confusion. The charge, as before, is that, for all that you know, your judgement that the machine had worked might be wrong because you might be the copy. But recall here our previous observation that the only person who could get this judgement wrong, in this respect, is your copy. You could never get this judgement wrong, as also noted above. The sense in which you might be the copy here is just that in which it might be the copy who was having these very experiences, and judging wrongly that the machine had worked. That your copy might get this judgment wrong is not a problem for you. Nor is it a problem for your copy, since, preferring to be deluded, as hypothesized, he would not care to get it right. So there is no issue here. We may compare this situation with the previous one where the copy would care to get it right. We saw there that you'd be forced to assume a split personality, à la Dennett's protagonist above, flitting between the perspectives of original subject and copy, the former wanting to declare that the machine had worked, the latter otherwise. Each would veto the other's predilection, as it were, and so you'd end up the proverbial ass, paralyzed on the matter of whether the machine had worked. You wouldn't be able to say, either way.

Consider the difference between these two questions, either of which might arise on the supposition that someone enters the machine and gives it a go:

and gives it a go:

The first question, in contrast, has a broader scope. It asks, not only what the second question is asking, but also whether the copy (should he awaken on Mars) would know whether the machine had worked or failed. And notice here that, while this latter question may be interesting in its own right, it is not relevant for our purposes. We don't essentially care whether the copy would be able to divine his true situation, should he awaken on Mars, but only whether the original subject, the person who originally entered the machine, would be able to do so. So the questions above are significantly different, and it seems to me that they have significantly different answers too.

I do agree that the answer to the first question is, “Always no,” i.e., that, as a general rule, should someone happen to use the machine, then the person waking up on Mars would not know—would be unable to tell—whether he was real or copy. This general claim should be relatively uncontroversial, and I believe that the skeptic would concur, so I will save a short discussion of its justification for later.

More controversially, I propose that the answer to the second question is, “Sometimes yes,” i.e., that, in certain cases where the machine is used, the person who enters the machine would know—would be able to tell—that the machine had worked, should he wake up on Mars. One such case is the one we are in the midst of, where the person who enters the machine is the sort of person who would be aghast at the thought of being the copy, etc., as detailed previously.

This proposal certainly requires justification, and my first point, to this end, is that someone skeptical of it, and who feels that the answer to the second question should (surely!) also be, “Always no,” may have conflated the two questions displayed above, or may have otherwise failed to see that there are two separable questions here. Thus, someone who begins by contemplating whether the person who originally entered the machine (should he awaken on Mars) would know whether the machine had worked or failed, may unsuspectingly slip into contemplating whether the person waking up on Mars would know whether the machine had worked or failed. After all, should the person who originally entered the machine rouse on Mars, he would be the person waking up on Mars, so it's easy to mix up the two questions.

A slip of this sort may have tainted the sceptical “concern” voiced above, which appeals to the fact that being the copy is indistinguishable—from the “inside,” from the first-person point of view—from being the original subject. This appeal to the first-person perspective is entirely natural: one imagines oneself entering the machine, thereafter waking up on Mars, and finds, in one's imagination, that one cannot tell—from the “inside,” from the first-person point of view—whether one is real or copy. And so one concludes that the answer to our second question above must be no. The trouble, however, is that the first-person perspective is unable to distinguish the two questions displayed above. One can certainly imagine waking up on Mars from the first-person perspective, but the supposition that one is the original subject cannot be captured within that perspective itself. So one can't really use the imaginative technique described above to get a handle on the second question, as opposed to the first: there would be no telling which of these two questions one was engaging with. Indeed, it would be more plausible to say that one was engaging with the first question, by means of this technique, since no information is provided concerning who is waking up on Mars here.

Indeed, it seems to me that if anything at all can be gleaned from this imaginative technique, it would be the answer to the first question above. And so it's not surprising that the answer one arrives at is, “Always no,” that being the correct answer to that question.previous observation that the only person who could get

The issue is whether the person who emerges from the transporter is the same person as the one who entered; or just a freshly-minted lookalike, the one who entered having died. For my purposes, I will assume—pace someone like Parfit—that this is a legitimate issue, concerning two genuinely distinct possibilities, the only question being which one is true. The line I wish to pursue, thus taking the question at face value, is whether the answer to it can be determined empirically.

Empirically speaking, what everyone agrees on is this: we cannot determine the answer “from the outside,” i.e., from a third-person vantage point. It would be futile to observe someone else enter the machine and thereafter “check” if that same person emerged on Mars: there would be no telling if the person who emerged was the same as the one who entered. The interesting question, however, is whether we can determine the answer “from the inside,” from the first-person point of view. At risk to your own life, could you not try the machine out for yourself in order to see what happens?

This simple first-person check does appear to work in at least one type of case. If there was such a thing as an afterlife, then, if the machine killed you, you’d find yourself waking up in some fiery place like purgatory (say), and you’d realize (let’s presume) that you were dead. Thus:

Kathleen V. Wilkes, Real People: Personal Identity without Thought Experiments. (1988), p. 46, n. 28.

Available at the Internet Archive.

Given Wilkes’s aversion to thought experiments, she may not have approved of my use of this passage.

This is Kathleen Wilkes, artfully highlighting the uncomfortable possibility conveniently left unmentioned in Star Trek. Her words are to our purpose too: if the transporter killed you, then you could discover this by trying it out, assuming there was such a thing as an afterlife. Of course, if there was no afterlife, then you’d learn nothing: you’d just lose consciousness and it’d be over. But the potential for falsification is clearly there since we cannot in general rule out an afterlife.

If falsification of teletransportation is thus possible, what of verification? What happens if the machine worked and really did “send” you to Mars? You’d press the button and find yourself waking up on Mars. Would this assure you in a parallel way that teletransportation was real and that you really had been transported to Mars? Take Parfit’s story above:

Would this satisfy Parfit himself, if no one else, that the machine had worked? Would it constitute an empirical verification of teletransportation?

As we know, the matter is not that simple, because of the following obvious snag. Even if the machine did work, and you did find yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether you were the person who entered the machine, or whether that person died, and you were just a freshly-minted lookalike with false beliefs of having previously entered the machine. After all, anyone—real or copy—who emerged on Mars would “remember” having earlier entered the machine on Earth. So you’d be none the wiser as to whether you were “real” or “copy,” and thus none the wiser as to whether the machine had really worked.

For example, in Dan Dennett’s story, a woman on Mars with a broken spaceship uses a teletransporter to get back to Earth. Upon reuniting with her daughter Sarah, it “hits her”:

So it seems that, if the machine worked, you could not discover this even by trying it out for yourself. This may be why the question is seldom discussed of whether teletransportation is subject to empirical test. At least where verification of the phenomenon is concerned—and this is arguably the more important case—the answer may be thought to be obviously no.

⚹

This may be thought to settle the matter but, in fact, I will suggest now that the foregoing sceptical thoughts are somewhat confused and essentially incorrect. If the teletransporter works, I believe that you can verify this by trying the machine out for yourself. Not always, as I will explain, but at least some of the time, when conditions are favourable in a certain way.

The alleged threat here is the false memory. As you wake up on Mars, the thought that you might be the copy with the false memory is supposed to give you pause. But for this possibility, you could just go by your memory of having entered the machine and judge that the machine had worked. But—wait—you might be the copy! Then your memory would be false and the machine would in fact have failed! You’d be in danger of making the wrong judgement here if you went by your “memory.”

This line of thought could use a little clarification, since it should be obvious that the only person, really, who could end up making the wrong judgment here is your copy, and not you. You yourself could never be “in danger” of judging wrongly that the machine had worked, since you were the one who entered the machine. The sceptic’s point, rather, is better expressed as follows. Being unable to tell whether you were real or copy, you'd be forced to assume a split personality, à la Dennett's protagonist above, flitting between the perspectives of original subject and copy, the former wanting to declare that the machine had worked, the latter otherwise. Each would veto the other's predilection, as it were, and so you'd end up the proverbial ass, paralyzed on the matter of whether the machine had worked. You wouldn't be able to say, either way.

Having clarified that, the weakness in this reasoning may perhaps be evident. It presupposes that your copy would be just as concerned (as you would be) about whether the machine had worked or failed, i.e., would care to know the answer, would want to make a reasonable judgment on the matter, would not want to get it wrong, and so on. Note that this presupposition is substantial in the sense that it was not built into our story. In contrast, that you, the person who originally entered the machine, would care about these things was given in the story: in particular, should the machine work, you'd want to know that it was really you who was waking up on Mars, and thereby that the machine had indeed worked. After all, you were trying to see if teletransportation could be verified in the first-person. But that your copy, should he awaken on Mars, would likewise be interested in knowing that he was, in fact, the copy, and thereby that the machine had failed, while consistent with our story, is not actually essential to it.

To see how this matters, imagine that your copy, should he awaken on Mars, would actually rather not know that he was the copy and that the machine had failed. This might be the case if, for instance, you yourself were the sort of person who would be aghast at the thought of being a copy, and would rather labour under the misapprehension that you were real than face the nightmare of being a copy. (Your copy, should he subsequently materialize, would then inherit this disposition.) Under these circumstances, the previous “threat” of the false memory would vanish. For—recall—what was supposed to give you pause, as you wake up on Mars, was the thought that you might be the copy with the false memory: there was a danger of “you” judging wrongly that the machine had worked if you went by your memory. But if the copy does not care about judging thus wrongly, this “danger” no longer exists. Nothing now stops you from going by your memory and judging that the machine had worked. In particular, the thought that you might be the copy would no longer stop you.

In a case like this, I submit that you'd be able to verify that the machine works, if it does work, by trying it out for yourself. You'd enter the machine, press the button, and, upon waking on Mars, would grasp (for the reasons above) that you may just go by your memory and judge that the machine had worked—which we may presume you to do. Your judgment would be bound to be correct, as before, because you were the one who entered the machine. Moreover, the correctness of your judgment would be no fluke: luck is nowhere involved. Given these considerations, it is natural to ask whether you may be said, in this case, not merely to have judged correctly that the machine had worked, but also to know that the machine had worked (and thus to have verified the reality of teletransportation). Having considered the matter carefully, I believe that the answer is yes, although this is not obvious and requires some justification. Notoriously, there is a gap between judging correctly and knowing, and it may seem that the gap is not bridged in our case. Consider, in particular, our previous concession that you'd be unable to tell, upon waking, whether you were the person who originally entered the machine or the copy with the false memory. This does not appear to be vitiated in our modified case. Thus, notwithstanding your distaste at the thought of being the copy, being the copy would remain indistinguishable from being the original subject, so how could you tell which one you were? And if you couldn't tell, then you wouldn't really know whether the machine had worked or failed. Granted, you'd be bound to judge correctly that you were the original subject and that the machine had worked, but, for all that you'd know, for all that you'd be able to tell, you'd be the copy with the false memory, laboring under the misapprehension that you were real.

⚹

This concern is indeed very natural, and virtually the first thing that comes to mind, but I believe that it also rests upon a confusion. The charge, as before, is that, for all that you know, your judgement that the machine had worked might be wrong because you might be the copy. But recall here our previous observation that the only person who could get this judgement wrong, in this respect, is your copy. You could never get this judgement wrong, as also noted above. The sense in which you might be the copy here is just that in which it might be the copy who was having these very experiences, and judging wrongly that the machine had worked. That your copy might get this judgment wrong is not a problem for you. Nor is it a problem for your copy, since, preferring to be deluded, as hypothesized, he would not care to get it right. So there is no issue here. We may compare this situation with the previous one where the copy would care to get it right. We saw there that you'd be forced to assume a split personality, à la Dennett's protagonist above, flitting between the perspectives of original subject and copy, the former wanting to declare that the machine had worked, the latter otherwise. Each would veto the other's predilection, as it were, and so you'd end up the proverbial ass, paralyzed on the matter of whether the machine had worked. You wouldn't be able to say, either way.

Consider the difference between these two questions, either of which might arise on the supposition that someone enters the machine

Would the person waking up on Mars know whether the machine had worked or failed?Note that the second question is the question of whether teletransportation can be verified by trying the machine out for oneself. It's also our question above of whether you'd know, upon waking up on Mars, whether the machine had worked or failed. Admittedly, our question involved some dramatization: we imagined you (in particular) getting into the machine, and thereafter waking up on Mars, but it's essentially the same question as the second one above. The question would arise for anyone who stepped into the machine and thereafter woke up on Mars, with you just being a helpful example.

Would the person who originally entered the machine (should he wake up on Mars) know whether the machine had worked or failed?

The first question, in contrast, has a broader scope. It asks, not only what the second question is asking, but also whether the copy (should he awaken on Mars) would know whether the machine had worked or failed. And notice here that, while this latter question may be interesting in its own right, it is not relevant for our purposes. We don't essentially care whether the copy would be able to divine his true situation, should he awaken on Mars, but only whether the original subject, the person who originally entered the machine, would be able to do so. So the questions above are significantly different, and it seems to me that they have significantly different answers too.

I do agree that the answer to the first question is, “Always no,” i.e., that, as a general rule, should someone happen to use the machine, then the person waking up on Mars would not know—would be unable to tell—whether he was real or copy. This general claim should be relatively uncontroversial, and I believe that the skeptic would concur, so I will save a short discussion of its justification for later.

More controversially, I propose that the answer to the second question is, “Sometimes yes,” i.e., that, in certain cases where the machine is used, the person who enters the machine would know—would be able to tell—that the machine had worked, should he wake up on Mars. One such case is the one we are in the midst of, where the person who enters the machine is the sort of person who would be aghast at the thought of being the copy, etc., as detailed previously.

This proposal certainly requires justification, and my first point, to this end, is that someone skeptical of it, and who feels that the answer to the second question should (surely!) also be, “Always no,” may have conflated the two questions displayed above, or may have otherwise failed to see that there are two separable questions here. Thus, someone who begins by contemplating whether the person who originally entered the machine (should he awaken on Mars) would know whether the machine had worked or failed, may unsuspectingly slip into contemplating whether the person waking up on Mars would know whether the machine had worked or failed. After all, should the person who originally entered the machine rouse on Mars, he would be the person waking up on Mars, so it's easy to mix up the two questions.

A slip of this sort may have tainted the sceptical “concern” voiced above, which appeals to the fact that being the copy is indistinguishable—from the “inside,” from the first-person point of view—from being the original subject. This appeal to the first-person perspective is entirely natural: one imagines oneself entering the machine, thereafter waking up on Mars, and finds, in one's imagination, that one cannot tell—from the “inside,” from the first-person point of view—whether one is real or copy. And so one concludes that the answer to our second question above must be no. The trouble, however, is that the first-person perspective is unable to distinguish the two questions displayed above. One can certainly imagine waking up on Mars from the first-person perspective, but the supposition that one is the original subject cannot be captured within that perspective itself. So one can't really use the imaginative technique described above to get a handle on the second question, as opposed to the first: there would be no telling which of these two questions one was engaging with. Indeed, it would be more plausible to say that one was engaging with the first question, by means of this technique, since no information is provided concerning who is waking up on Mars here.

Indeed, it seems to me that if anything at all can be gleaned from this imaginative technique, it would be the answer to the first question above. And so it's not surprising that the answer one arrives at is, “Always no,” that being the correct answer to that question.previous observation that the only person who could get

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2024  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine